Artisans with Heart, Gifts with a Conscience

Susan Gomez recalls waiting nervously on an isolated road in southern Arizona for her ride across the border to Mata Ortiz, Mexico. The air was thick, and she could hear thunder in the distance.

Her business partner, Mayra Castellanos, had implored her not to go. A native of Juarez, Mayra was familiar with the big-city narcos culture that was seeping into rural villages like Mata Ortiz.

But Susan was determined to make her first trip to meet local Mexican artisans whose livelihoods were endangered by the growing drug violence. Just a few years ago, "busloads of tourists were driving into Mata Ortiz twice a day to buy pottery from a thriving collective of 600 artisans. Now they are destitute because people are afraid to travel, and many are leaving their craft."

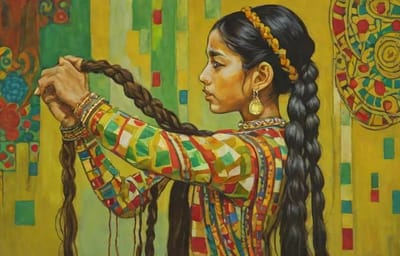

Preserving traditional Mexican art forms is central to the mission of Amigos Art & Pottery, a retail social enterprise Susan and Mayra founded to help artisans transcend obscurity and poverty by showcasing and selling their wares for a fair price in the US.

"Precio justo" is the goal, says Mayra – the "just price" that enables artists to live off of their skills and continue stylistic traditions that are thousands of years old rather than settle for transient jobs in climates of conflict.

Investing in a Sustainable Future

Mayra and Susan developed an interest in indigenous artists a few years after meeting in a community college pottery class. "In pottery, you make something with nothing," says Susan. "We were inspired by the beauty of that."

Both women also identify as Mexicanas and were drawn to the ornate work of their ancestors. As they practiced different techniques and styles in class, Susan and Mayra stumbled upon contemporary artisans in Mexico – and learned of the inequities they faced in the art market.

"We know of an artist who spends months on a single stunning piece of pottery. He might get paid $50," says Susan. "Then that same piece would appear in a gallery in San Diego or Palm Springs and sell for $3500."

The potters of Mata Ortiz, a mountainous village in Mayra's home state of Chihuahua, use age-old techniques to fire their pottery. "They cut the wood from surrounding areas, and heat the pots underground like their ancestors," she shares. "They are running out of wood."

The process is unsustainable and often yields pots that are too fragile to transport even locally. This means months of hard and intricate work might all go to waste during the final stages of production.

"If their pieces fetched higher prices, the artists could invest in other types of clay and kilns that fire higher," explains Susan, using pottery jargon for "cooking" at the right temperature.

One barrier to getting a precio justo is that mass production has taught consumers to view a vase or a bowl as commodity – not a work of art. That's why the Amigos Pottery website looks more like a gallery than a store, with rich storytelling about the people behind the wares. "This is about people, not products," says Susan.

The Anonymity of Community

One of the artists that left an impression was Miguel, whom Susan and Mayra met when they traveled further south to Capula, Michoacán, a town famous for ceramics. Miguel sculpts clay Catrinas, the iconic female skeletal figure that symbolizes the Mexican Día de Muertos or Day of the Dead.

"There are Catrinas for sale everywhere in Capula, but Miguel's are special," says Susan. "He brings the faces to life and his work is very detailed." Unlike other Catrinas, which are almost a commodity for tourists, Miguel's work features unique motifs that he says come from deep within his imagination.

"Miguel is very quiet and serious, but when we asked him about his art, he lit up," Mayra recalls. "These artists, their houses are poor, but they are happy, grateful, and they love their work."

Less than an hour's drive from Capula, Susan and Mayra found the same joy in the copper artisans of Santa Clara del Cobre, a small town recognized nationwide for its cultural and artistic significance. Here, the Purepecha indigenous people have been working with copper since before the Spanish arrived in Mexico in the early 1500s.

Struck by the craftsmanship and beauty of the urns, decorative plates, and vases, Susan and Mayra included them in their collection. "We ran out of luggage," Susan says.

What surprised the women most on their quest for personal stories was the communal nature of artistry in the villages. In Mata Ortiz, multiple generations are involved in firing exquisite pottery. The older members shape the pots, the kids run up the hills to harvest indigo and other dyes, and younger artisans with sharp vision etch the ancient patterns.

"In western culture, art is about the individual," says Mayra. "The artists we met in Mexico like Miguel — they don't even sign their work. It's about the community."

"It's our priority to share these stories and help these artisans preserve their legacy because that is what they care most about," Susan adds.

And the community is doing its part to ensure that Amigos Pottery succeeds in its mission.

The men who picked Susan up that night to drive her to Mata Ortiz? They were indigenous artists. She recognized the driver as Salvador Baca, a renowned master potter whose pieces have appeared in museums. "I've seen this man's work in books and here he is driving us in this 1950s truck through pouring rain."

"It means so much to them that we visit and feel safe doing it," Susan says. "We are Amigos Pottery, Artesanos con Corazón — Artisans with heart."

Seems more like family.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.